In the past, banks built themselves from the inside out—and for decades, it worked. Products were developed around a sturdy core banking system and rigid business process to ensure security and trust, distributed through branch networks, and only then wrapped in a customer experience and brand veneer. But those days are over because customers and the market demand the opposite. Today’s Fintech upstarts and digital-first neobanks have flipped the model on its head, designing their institutions from the outside in. To stay competitive in the digital age, traditional banks will have to consider the unthinkable: turning their entire business architecture upside down.

In the pre-digital era, banking products were largely undifferentiated commodities. Most institutions offered the same accounts, loans and transactions, competing mainly on interest rates and fees. Banks were built from the core outward—strengthening balance sheets, managing risk and scaling distribution—while customer experience was often an afterthought, since alternatives were limited.

High barriers to entry reinforced this model. Building a bank required heavy investment in branches, licenses, compliance, staff and years of preparation, which kept competition slow and scarce.

The digital era has dismantled those barriers. Fintechs can launch in months using third-party tech stacks, APIs and cloud platforms instead of decades of infrastructure. Even individuals can issue tokens or digital assets in minutes. The only real requirement now is delivering clear value to a customer segment.

This shift has intensified competition. Customers can switch providers with a few taps, and they expect seamless experiences, emotional connection and alignment with their values. Competing on process and price alone is no longer enough.

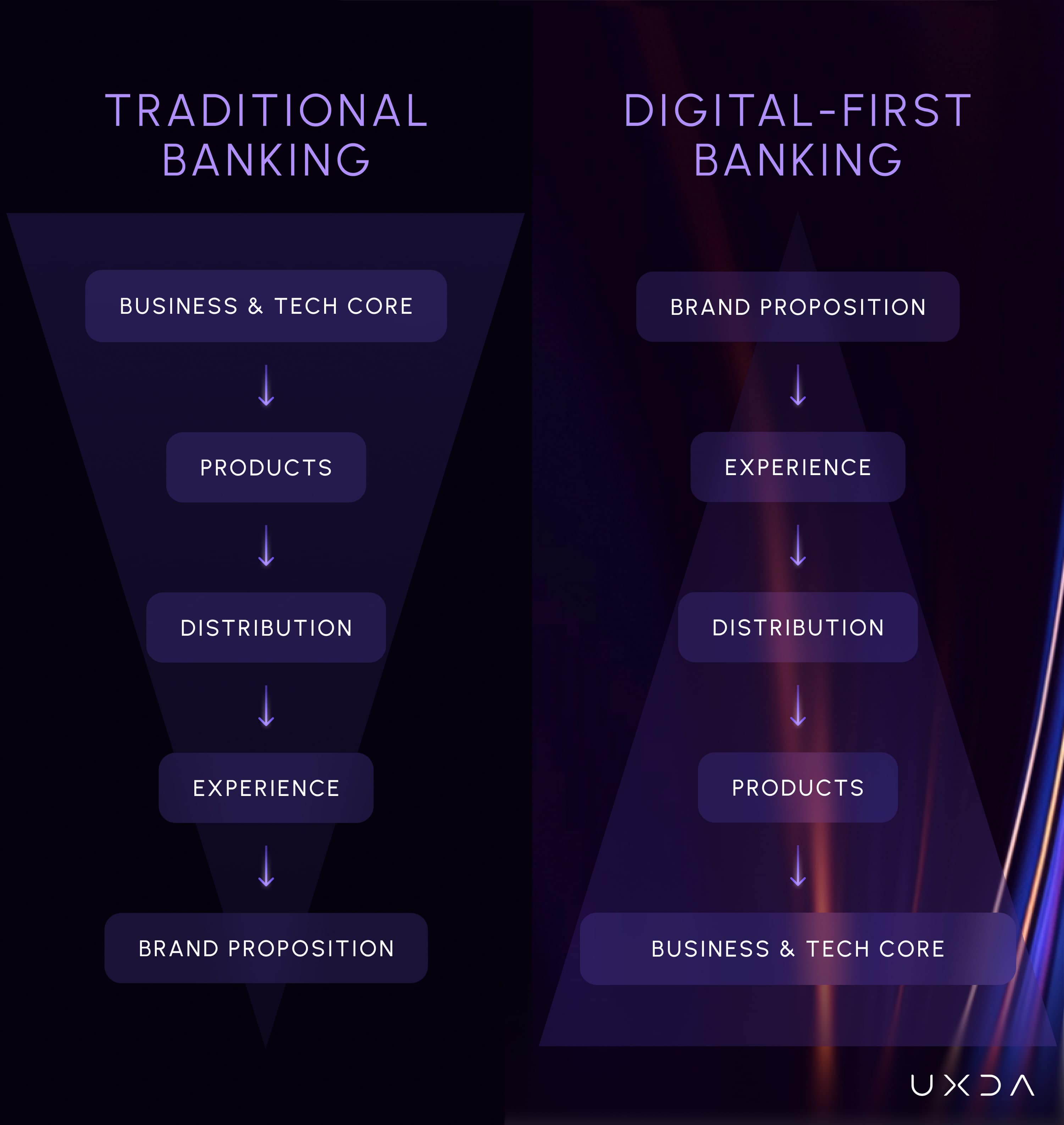

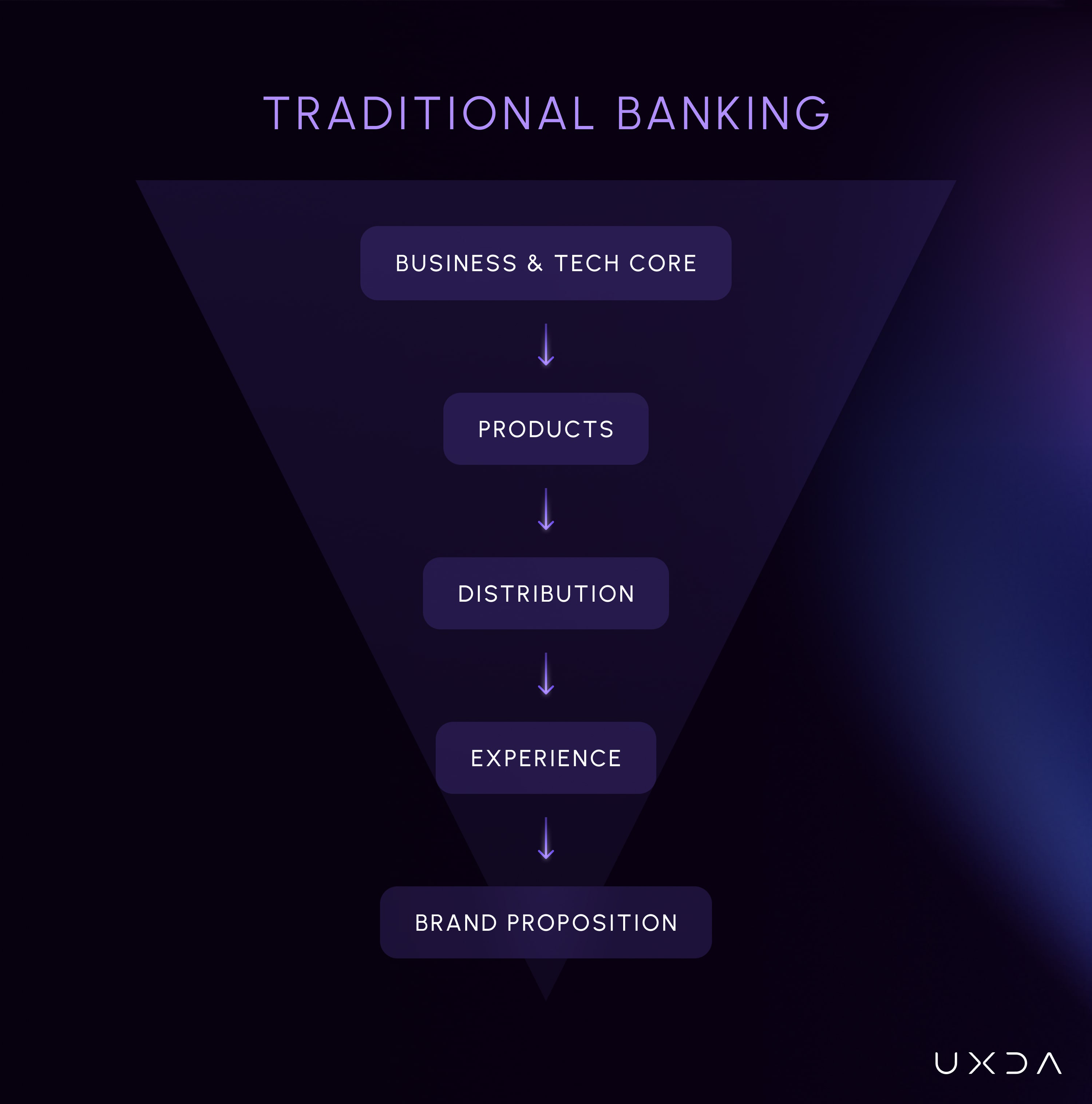

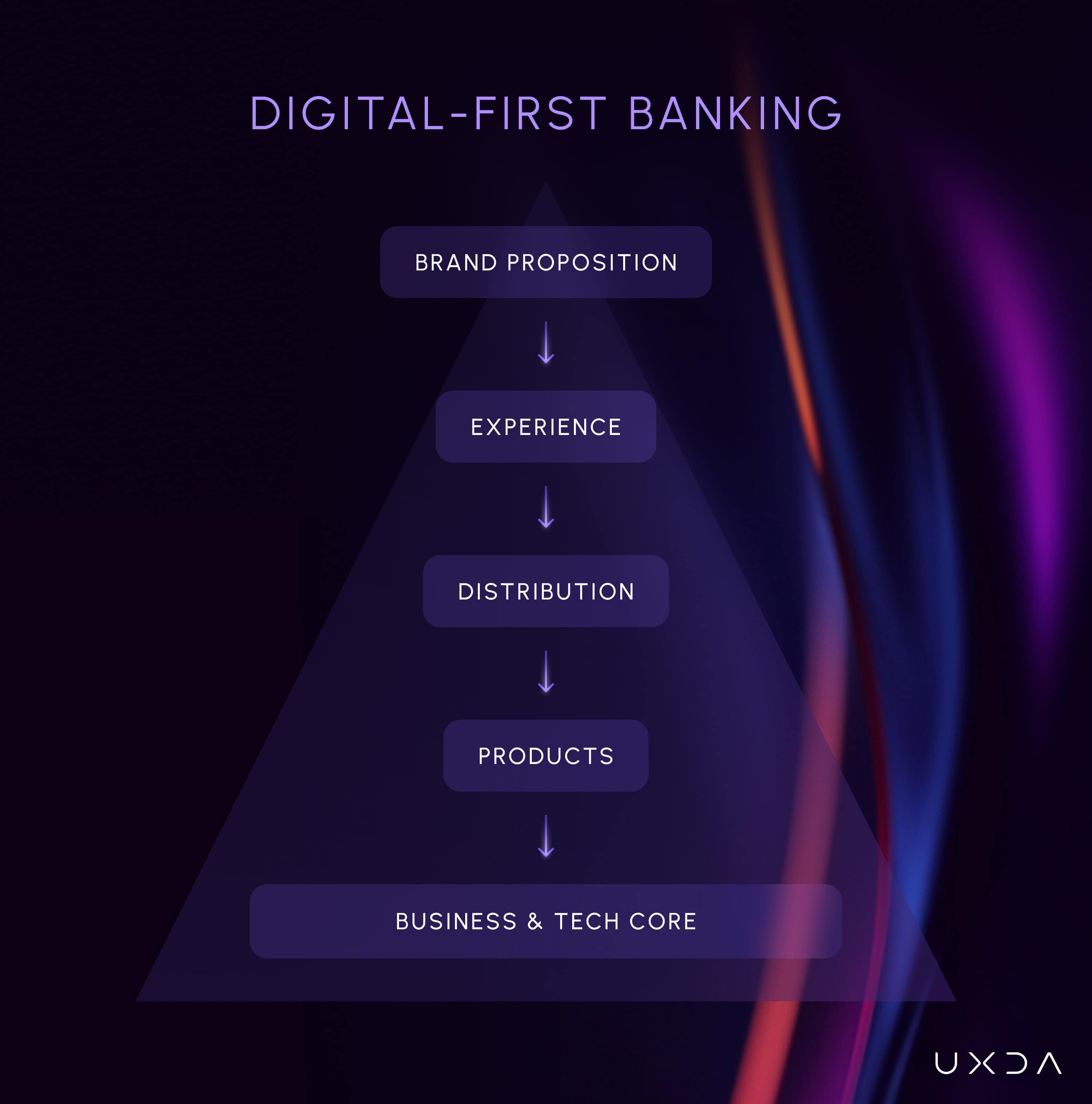

Traditional banks still operate inside out—starting with internal systems and processes, then building products, distribution, experience and, finally, brand. Fintechs invert this logic. They begin with purpose and customer promise, design engaging experiences, choose distribution that meets customers where they are and then build products and core technology to support that ecosystem.

What differentiates challengers is not a new app or feature, but a radical inversion of business logic. To stay relevant alongside tech giants and digital-first competitors, banks must shift from compliance-first to purpose-led, from process-driven to genuinely customer-centered. That requires rethinking legacy systems, governance and culture—placing customer experience at the core of strategy, not at the periphery.

Inside-Out vs. Outside-In Banking Architecture

In the banking industry, architecture is more than just IT infrastructure—it encapsulates how a bank’s business is structured and how value flows from the organization to the customer. So, what do we mean by “inside-out” architecture?

- Traditional (Inside-Out) Model: Business Core → Products → Distribution → Experience → Brand.

The bank’s core systems and internal processes are the starting point, dictating what products can be offered. These products are then pushed out through various distribution channels (e.g., branches, call centers, online banking, etc.), upon which a customer experience is built. Finally, the bank’s brand wraps around this stack, often as a marketing layer.

By contrast, digital-native banks and Fintechs embrace an “outside-in” architecture: - Digital-First (Outside-In) Model: Brand → Experience → Distribution → Products → Business Core.

The digital neobank or Fintech begins with a compelling brand purpose, proposal and identity, using it to invent a differentiated customer experience through unique services. This drives decisions on distribution, delivering services through the channels that best fit the desired experience (mobile apps, APIs, etc.). The neobank then develops or curates products that serve the customer needs identified through the desired experience. Finally, the core systems and key business processes are architected or adapted to support those products and services.

The inversion of these models represents a fundamental shift in business logic adapted to competition in customer experience. If the traditional inside-out approach is often “We build it, and customers adapt to us,” then the digital outside-in approach is “We understand the customer’s needs, and we fit our purpose and provide the best solution in the market.”

The inversion of these models represents a fundamental shift in business logic adapted to competition in customer experience. If the traditional inside-out approach is often “We build it, and customers adapt to us,” then the digital outside-in approach is “We understand the customer’s needs, and we fit our purpose and provide the best solution in the market.”

This outside-in philosophy is evident in how digital neobanks and Fintechs prioritize brand and user experience at the forefront, using them to pull through the rest of the value chain. It’s a move from product-centric to customer-centric banking, and from a focus on internal constraints to external expectations.

Having contrasted the two architectures, we can distill the fundamental differences in business logic:

- Inside-Out vs. Outside-In Mindset: Traditional banks prioritize internal constraints and then project outward; Fintechs and digital banks prioritize customer outcomes and work backward to internal operations.

- Process-Driven vs. Purpose-Driven: The traditional model is driven by established processes and compliance checklists (stability first), whereas the digital model is driven by a clear purpose and customer experience goals (value first).

- Product-Centric vs. Customer-Centric: Traditional banks focus on products and sales (often pushing what they have to customers), while digital players focus on customers and their needs (developing offerings tailored to those needs).

- Compliance-First vs. Innovation-First (with Compliance by Design): Incumbents often introduce compliance at the expense of convenience (a check-the-box mentality), whereas challengers aim to embed compliance into a smooth process so that innovation and compliance can coexist (e.g., using AI to automate KYC without burdening the user).

- Siloed Organization vs. Agile Teams: The traditional banking structure by departments and products creates fragmentation (each department “guards its slice” of the customer experience), in contrast to digital banking’s cross-functional teams aligned to customer journeys or segments, enabling more cohesive and rapid development.

- Periodic Change vs. Continuous Improvement: Legacy institutions roll out big changes infrequently (e.g., big IT projects, annual product updates), whereas digital banks are in continuous beta mode—constantly updating and deploying weekly or even daily enhancements.

- Transactional Relationships vs. Relational Engagement: The traditional approach often treats banking as transactions to process (the relationship is defined by account openings, loan disbursements, etc.), while the digital approach treats banking as an ongoing engagement (the relationship is nurtured through ongoing insights, recommendations and support, extending beyond simply transactions).

Traditional Banking Architecture: An Inside-Out, Process-Driven Model

Traditional banks have been built as process-driven, compliance-first organizations, structured primarily around internal operations and product silos. In the inside-out model (Core→Products→Distribution→Experience→Brand), each layer of the business is developed from the inside company moving outward to market, resulting in a bank that often projects its internal structure onto the customer.

Underlying this architecture is a culture that values process, control and risk mitigation above all. Traditional banks have long histories as operations-centric, process-driven organizations.

Banks pride themselves on robust procedures (for credit approval, transaction processing, etc.) and compliance rigor to meet regulations. Decisions tend to be made by committees, and innovation follows a checklist. This culture is effective at minimizing errors and avoiding compliance breaches; indeed, it has kept banks reliable and safe for generations. However, it also creates silos and slows response to change. Innovation is often relegated to a specific team or lab, rather than infused in everyday operations, because the prevailing mindset is to “do things the way we’ve always done.”

Front-line employees in a traditional bank are trained to follow scripts and processes rather than to deviate in service of a unique customer request. In summary, the inside-out bank is organized for regulatory compliance and efficient mass processing first, and only then for customer service or innovation.

A traditional bank often delivers a mediocre or uneven customer experience despite its best intentions. The approach is inside-out: design the product and processes first, then impose them on the customer. The ensuing consequences can be seen in many legacy institutions: slow product launch cycles, user interfaces that lag modern expectations, difficulty personalizing services and a reliance on customers to navigate bank-centric procedures.

For example, lengthy form-filling, in-person signatures or fragmented online services are all telltale signs of process-first design. Compliance requirements, while vital, are frequently implemented in a way that creates friction for the customer (think of cumbersome Know-Your-Customer checks or multi-step logins). The bank’s internal imperatives (e.g., completing forms correctly, collecting data for regulators) outweigh the goal of a frictionless journey.

It’s important to note that the inside-out model was logical for its time. In an era when banking was defined by physical records and in-person interactions, optimizing the core and standardizing products achieved stability and scale. Customers had fewer alternatives and would tolerate inconvenience as the price of accessing financial services. But as we’ll see, the digital age has upended this dynamic, offering customers abundant choices and raising expectations, while new entrants have shown that a different architecture is possible.

The fundamental logic of this model today can be described as follows:

1. Core Systems and Processes Dictate Offerings

Legacy banks start with their core—often decades-old core banking systems and tightly regimented processes for handling transactions, risk and compliance. The capabilities and limits of the core heavily determine what products the bank can offer.

Traditional cores are typically monolithic and inflexible, meaning product features and rules are constrained by what the core can support. This inside-out logic leads banks to offer standardized, one-size-fits-all products, because the core was designed for broad, traditional use cases. In the past, this was sufficient when banking was about mass-produced services and scale efficiency.

2. Product-Centric Organization

Legacy banks are structured around product lines (e.g., deposits, loans, credit cards, investments), each with its own P&L, managers and often separate IT systems. Under the inside-out model, products are developed to meet internal goals—profitability, compliance and regulation—rather than unmet customer needs.

Strict policies and committees ensure safety and compliance but slow innovation, resulting in infrequent, incremental updates. Historically, banks competed through the “6 Ps” (people, place, product, price, promotion, process), with product, process and price at the core, while customer needs remained secondary.

3. Distribution Before Experience

In the traditional architecture, distribution channels (e.g., branch networks, call centers, ATMs and more recently online banking portals with mobile apps) were built out as the means to reach customers. The bank’s strategy often prioritized distribution scale, e.g. “more branches equals more deposits.” The customer experience was an afterthought in many cases, layered on once the channels existed.

For example, a bank would roll out an online banking website to distribute its products digitally, but the user experience of that site might be clunky or purely functional. This is because the experience was often designed by IT and operations teams to mirror internal processes (inside out), rather than by designers empathetic to customers.

An inside-out mindset might produce an online account opening process that exactly follows the paper form and compliance checklist, rather than a streamlined digital journey. The end result is that many legacy banks ended up with fragmented experiences across channels, reflecting their organizational silos.

4. Experience as an Afterthought

In the inside-out model, the customer experience is not designed upfront but layered on top of existing products and distribution. Rather than shaping the journey around customer needs, banks often retrofit experiences to align with their internal processes and compliance requirements.

In practice, the “experience” is often reduced to user interfaces that deliver basic and generic functionality rather than a coherent journey. It is shaped more by IT constraints and product silos than by customer empathy. For instance, logging into a mobile app may involve outdated authentication flows dictated by legacy systems, while payment or transfer processes force customers through multiple confirmation steps because that’s how the core banking system processes them internally.

As a result, the digital experience layer in the Inside-Out model tends to feel like a patchwork of forms and portals rather than a purposeful, human-centered product design. Customers experience friction, inconsistency and lack of personalization, which erodes satisfaction and trust despite the bank’s intentions to “add” an experience on top of its operations.

5. Brand as Veneer

Finally, in this model, brand is the outermost layer, often treated as a marketing function somewhat detached from day-to-day product delivery. Banks have relied on brand reputation (particularly trust, safety and longevity) built over decades, but this brand promise does not always translate into the actual digital product experience.

There is frequently a gap between brand vision and user reality. It’s not uncommon to see a bank advertise itself as “customer-first” or “innovative” in glossy branding campaigns, yet its mobile app greets users with a clunky login and error messages from another era. Indeed, research shows many banks emerge from the boardroom with bold strategies and brand promises, only for those to dissolve into a patchwork of vendor widgets and generic flows by the time they reach the customer’s screen.

The brand exists in brochures and ads, but the lived experience is often generic. This disconnect is a direct outcome of an inside-out approach: the brand is applied at the end, rather than ingrained through the experience design from the start.

Next-Generation Digital Banking Architecture: An Outside-In, Purpose-Led Model

Fintechs and digital-first banks (aka “neobanks”) were born in a different paradigm. They built themselves as purpose-led, customer-centered organizations. In the outside-in architecture (Brand→Experience→Distribution→Products→Core), the design flows from the outside (the customer and the brand’s promise to that customer) inward to the core operations. The business logic here is: “Understand what customers value, deliver it in a delightful way, and only then build the internal capabilities needed to support that.”

The culture in Fintechs and digital-first banks is built around customer-centricity and innovation. These organizations often hire talent from technology and e-commerce backgrounds, bringing in a mindset of user experience, data analytics and rapid iteration. The leadership in such banks evangelizes purpose and customer satisfaction as the north star.

Success is measured with metrics like customer satisfaction (CSAT), NPS, active user rates and engagement time—not just traditional finance KPIs. Fintech teams celebrate customer delight and advocacy. They proactively seek customer feedback through in-app prompts, community forums and usability tests and incorporate the feedback into product improvements. The organizational structure is flatter and more agile, empowering teams to make decisions quickly in response to customer needs rather than waiting for top-down directives.

Risk is managed in a more dynamic way: instead of zero tolerance for any misstep (which can paralyze innovation), Fintechs focus on controlling risks through technology (e.g. advanced fraud detection algorithms, automated compliance checks, etc.) and testing, allowing more freedom to try new approaches safely. The mantra is often “solve for the customer, and the rest (e.g., revenue, loyalty) will follow.”

Purpose-led means employees are rallied around a mission, which can be a powerful motivator and also a compass when making trade-offs. For instance, a purpose-led Fintech might willingly forgo certain fee revenues if eliminating those fees aligns with their promise of helping customers save money—a decision a traditional bank driven solely by short-term profit might not take. Yet, in the long run, this builds trust and loyalty that serve to drive sustainable growth.

Customers of Fintechs often perceive them as a “partner” in their financial lives rather than just a faceless institution. The app or website is viewed as a helpful tool—even an enjoyable one—rather than a necessary evil. The emotional connection and trust can be much stronger.

It’s important to note that outside in does not mean ignoring risk, competition or profitability. Rather, it means finding new ways to manage them. Fintechs do it with advanced RegTech and data-driven monitoring. But they approach these goals via customer-centric innovation: for example, they may generate revenue through subscription fees for premium services that customers willingly pay for because they see clear value, instead of hidden fees that cause resentment.

Fintech and neobanks’ cost structures are usually leaner thanks to automation and digital channels, allowing competitive pricing. In essence, the outside-in model proves that being customer-centric and profitable can go hand in hand, but it requires reimagining how a bank operates from top to bottom.

Key characteristics of this model include:

1. Purpose and Brand Drive Strategy

Most Fintechs start with a clear purpose or mission—a specific problem to solve or a segment to serve—which forms the core of their brand identity. This could be a mission like “make banking fair and transparent” or “help young professionals achieve financial wellness.”

The brand in a Fintech is not an afterthought; it is foundational. It informs everything from the tone of communications to the features offered. Being “purpose-led” means these banks define success not just in terms of short-term profits, but in fulfilling a meaningful promise to customers and society.

Today’s consumers expect empathy and purpose-driven business from their financial institutions. Neobanks leverage this: for example, some position themselves as champions of the underbanked or as lifestyle brands that help with budgeting and life goals. This purpose-driven approach provides focus and differentiation. It also guides decision-making: choices are tested against the question “does this serve our customer purpose?” rather than “does this fit our existing process?”

2. Experience as the Starting Point

Anchored by a strong purpose, digital banks design the customer experience (CX) upfront, effectively making the user journey the product. They often employ human-centered design and research to map out what an ideal banking experience looks like for their target users. This includes everything from seamless onboarding (e.g., opening an account in minutes from a mobile phone) to daily interactions (e.g., real-time spending notifications, personal financial insights) to problem resolution (24/7 in-app chat support).

The experience is crafted to be intuitive, engaging and even emotionally resonant. A key mindset shift here is that the experience is the brand—every digital interaction is considered a brand touchpoint that must reflect the bank’s values. Customers no longer experience a bank through marble lobbies or printed brochures; they experience it through six-inch screens in 30-second bursts. Every digital micro-interaction is a brand impression with measurable revenue impact.

Neobanks and Fintechs embrace this reality, treating UX design as a core competence, not an add-on or "package design." They strive for frictionless, even delightful interfaces. Importantly, they also bake trust and compliance into the UX in creative ways (e.g., using biometrics for security without adding extra steps or explaining security measures in plain language) so that safety doesn’t come at the cost of usability.

The outside-in approach means compliance requirements are met by designing better processes that satisfy rules with minimal customer burden, rather than by making the customer do the heavy lifting. The overall result is often dramatically higher customer satisfaction.

3. Omnichannel Distribution on Customer Terms

With experience design leading, decisions about distribution flow naturally. Rather than forcing customers into certain channels because “that’s what the bank has,” neobanks choose channels based on customer preferences. Unsurprisingly, most emphasize mobile apps and web platforms as primary channels, given the always-connected behavior of modern consumers.

Most decline physical branches entirely, but some might maintain a very light physical presence or partner with retail agents if needed, but the principle is to be “digital by default.” This dramatically lowers cost-to-serve (digital banks often operate at cost levels 5-8 times lower than traditional peers) and allows scaling without physical constraints.

It also means distribution can be more integrated. For example, a customer can sign up via a mobile app, get service via in-app chat and access accounts via a web browser interchangeably. The channel strategy is unified by the desired experience: the aim is seamlessness.

In an outside-in architecture, channels are seen as facets of one unified service, not as separate silos. A customer should perceive the same brand experience whether on a phone, laptop or talking to support. Many Fintechs have achieved this consistency by building their tech stack for omnichannel delivery from scratch.

Moreover, Fintechs leverage new distribution paradigms like ecosystems and embedded banking. For instance, they might offer banking services via APIs to be embedded in other platforms so the “distribution” might even be through a partner’s app. This approach—often called Banking-as-a-Service—is an outside-in strategy to meet customers in contexts that suit them. Overall, distribution in the digital model is flexible and customer-driven, rather than institution-driven.

4. Agile, Needs-Based Product Development

Perhaps the most striking difference is how products are developed in the outside-in model. Instead of starting with what the core and business processes can do, Fintechs and neobanks start with customer needs and then figure out how a product or feature will solve it.

They treat their service as a constantly evolving product shaped by user feedback and analytics. Using agile methodologies, they can release new features or tweaks in days or weeks, test them with users and refine them continuously. This is a sharp contrast to the long release cycles of traditional banks.

Neobanks often offer a pared-down set of core products (e.g., a checking account with a debit card, a savings account and maybe a credit line or simple loans) that are heavily augmented with features that solve daily pain points (like instant notifications, fee-free overdrafts up to a point, savings rules and budgeting tools). They also integrate third-party products via APIs if it enhances the customer journey. For example, they might partner with an investing app rather than building their own investment product, if that aligns with customer needs.

Personalization is a hallmark: products may be dynamically tailored by algorithms (for instance, credit offers tuned to individual behavior). Customer data is leveraged to anticipate needs, so the “product” feels less like a static account and more like a responsive financial companion. All of this requires the bank’s internal teams to be interdisciplinary (combining tech, data and customer insight) and quick to respond.

Digital banks thus break down the old silos; small, autonomous teams own customer journeys or segments rather than individual products. This allows rapid innovation focused on delivering customer value. A culture of experimentation prevails—new ideas are prototyped, A/B tested with subsets of users and scaled if successful. Failure in a test is not seen as a disaster but as learning, which is a significant cultural shift from traditional banking.

Notably, compliance and risk teams in digital organizations are often embedded into product squads to ensure that as new ideas are developed, they remain within regulatory guardrails. This is in stark contrast to legacy banks in which compliance might veto ideas late in the process. By integrating risk considerations early, digital banks can be both innovative and compliant, achieving the “outside-in” ideal of meeting customer needs while satisfying regulatory requirements. (This approach echoes advice from consultants: build risk and compliance into design rather than layering them later.)

5. Flexible, Modern Core Technology

Finally, at the foundation of the outside-in model, is the core system, but it is a very different beast from legacy cores. Many digital banks operate on modern core banking platforms that are cloud-based, API-driven and modular. Some even pursue a “coreless” banking approach, in which no single monolithic system holds all deposits/loans, but rather a mesh of services and databases coordinated to perform core functions.

The guiding principle is that technology should enable the desired customer experience, not constrain it. This often means using microservices architecture in which each service (payments, account ledger, user authentication, etc.) can be updated or scaled independently. It also requires an API-first mentality in which every functionality is exposed via APIs, allowing easy integration with external partners and ecosystems.

The advantage is agility: deploying updates or new services without downtime and the ability to plug in third-party Fintech solutions if they provide a better component (for example, using a third-party KYC service via API to speed up onboarding). Moreover, a modern core typically processes in real-time (or near real-time), which is essential for delivering up-to-the-minute information to customers.

Traditional cores that do batch processing (end-of-day updates) cannot support the level of instant insight customers now expect (e.g. seeing a transaction in your app the moment you swipe your card). Neobanks ensure their technology delivers that immediacy. They also leverage the scalability of cloud to accommodate rapid customer growth or usage spikes, something that can be challenging on older on-premise systems. In terms of cost, modern cloud-native cores can be more cost-effective at scale and free up IT resources from maintenance to innovation.

Many industry experts foresee all banks moving to modern, cloud-based cores within the next decade. While incumbents struggle with core upgrades, digital banks had the fortune of starting fresh with new tech. This gives them a competitive edge in rolling out features quickly and integrating with the digital ecosystem (payments networks, Fintech apps, open banking interfaces) more seamlessly.

Implications on Strategy

Strategy formation and focus diverge significantly between traditional and digital-first banks due to their architectural orientations.The inside-out vs. outside-in architecture drives a very different strategic mindset.

Traditional banks strategize from the inside: how to leverage our capabilities, products and channels to meet business goals, adjusting to customers only as an afterthought or when competition forces it. Digital banks strategize from the outside: how to meet customers’ goals and fulfill our purpose in a way that differentiates us, and then how to align our capabilities to support that.

For a legacy bank executive, shifting to an outside-in strategy may require redefining success beyond classic financial metrics to include customer metrics and being willing to disrupt their own established products in favor of new models. We will later discuss how a traditional bank can begin to adopt this strategic posture as part of its transformation path.

Traditional Bank Strategy: Product and Efficiency Focus

Planning centers on extending what exists: grow product volumes, cut costs, meet regs. Strategy is anchored in assets (e.g., branches, product suite, balance sheet) and favors product/pricing/distribution plays. Roadmaps are multi-year and waterfall; risk appetite is low, protecting the status quo rather than adapting to new expectations.

Customer experience has traditionally been a secondary consideration in strategy, often mentioned in vision statements, but not truly at the core of strategic decision-making. As evidence, a study of banks’ digital efforts showed many have polished strategic plans with buzzwords like “customer-centric” and “digital-first”, yet on execution the plans translate into the same old product pushes and generic experiences. This indicates that even when strategy documents talk about transformation, the actual strategic focus of many legacy banks remains tied to internal metrics and processes.

Digital Bank Strategy: Customer and Differentiation Focus

Digital-first neobanks, being outside-in, formulate strategy in a nearly opposite fashion. Their strategy starts with customer and market insight. They ask: Who are our target customers and what do they need? What pain points can we solve? How can we differentiate through experience? The strategic focus is on delivering unique value to the customer, knowing that growth and financial results will follow if they succeed in that mission.

For example, a neobank might strategically target tech-savvy millennials who are frustrated with big banks and craft its entire offering and marketing around being the most loved, convenient bank for that demographic. All strategic initiatives—whether it’s launching a new budgeting tool or expanding to a new geography—will be justified by how they enhance customer value and advance the brand promise.

Furthermore, digital bank strategies are often iterative and flexible. These banks operate in fast cycles, continuously measuring customer feedback and market trends and adjusting the strategy accordingly. It’s not uncommon for a digital bank to update its strategic priorities annually or quarterly, as they gain insights from data. This is possible because their organizational model (agile teams, modular tech) supports rapid pivots.

In sum, the strategy of digital banks is about outside-in value creation: find a niche or broad need in the market and address it better than anyone else through superior experience and technology.

Competitive and Market Approach

The differing architectures also influence how banks view competition and partnerships strategically. Traditional banks, coming from a position of incumbency, often see competition in terms of market share battles with other banks and encroachment by Fintech as a threat to be defended against. Their strategies might involve lobbying for regulatory protection, acquiring Fintech startups as a defensive move or using their scale (e.g., pricing power) to undercut new entrants. Their inside-out orientation sometimes blinds them to indirect competition—for example, customers comparing their service not just to other banks but to Big Tech user experiences.

Digital banks inherently understand that the competitive benchmark is the best customer experience out there, regardless of industry. Banking customers now compare their bank’s service to their experiences with top tech brands and e-commerce, not just to other banks. Thus, digital bank strategies often involve outpacing customer expectations, not just rival banks.

Metrics and KPIs

Strategic focus is also evident in what metrics banks prioritize. Inside-out institutions heavily track product sales, transaction volumes, branch performance, etc., and of course compliance metrics (regulatory ratios, audit findings). Customer satisfaction might be tracked but historically was not a primary board-level KPI. That’s changed in recent years, but the cultural inertia remains.

Digital-first banks elevate metrics like NPS, customer churn rates, daily active users and customer lifetime value as equal to or more important than product-centric metrics. They strategically aim to maximize engagement and lifetime value, rather than just immediate product sales. This fundamental difference in strategic outlook—short-term product sales vs. long-term customer relationship value—shapes many other decisions.

It’s notable that in some legacy banks, incentives for managers are still tied to product or unit performance, which can conflict with customer-centric goals, whereas in digital banks the incentives are more aligned to overall customer growth and satisfaction.

Implications on Product Development and Innovation

The architectural approach of a bank heavily influences how it develops and innovates products. The contrast between process-driven traditional banks and agile digital banks is perhaps most evident in their product development methodologies and innovation culture. The product development paradigm of an inside-out bank is akin to a large ship that changes course slowly, while an outside-in bank is like a fleet of speedboats constantly adjusting course.

It should be acknowledged that traditional banks are trying to adopt agile methods and have had some successes in narrow areas. But often, they encounter internal resistance—cultural, procedural or due to legacy systems—that limit the effectiveness of those methods. For instance, a bank may declare it has “agile squads,” but if those squads still depend on a core system team’s yearly release or a risk committee’s monthly meeting for approvals, their velocity is throttled. True agility often demands deeper changes in architecture and empowerment, which ties back to the need for an architectural inversion.

Traditional Banks: Waterfall Development and Siloed Innovation

Legacy banks still rely on slow, waterfall-style product cycles: lengthy approvals, siloed handoffs, compliance-heavy testing and big-bang launches. This entire cycle can take years. By the time the product is launched, customer needs may have shifted, or the feature may already lag behind what Fintech competitors offer. Moreover, because departments are siloed, each step is owned by a different team (e.g., product, then IT, then risk/compliance, etc.), resulting in what has been termed the “throw it over the wall” approach. This fragmentation means the final product can feel disjointed and is rarely optimal from a user perspective.

Development pipelines (as in traditional institutions) are optimized for stability and compliance, not rapid iteration. UX audit requires cross-department sign-offs; usability sessions fight for budget; QA runs after launch instead of before. In other words, the whole system is geared toward making sure nothing goes horribly wrong (which is important) rather than ensuring something is wonderfully right for the customer. Innovation in such environments tends to be managed in isolation.

Many banks set up innovation labs or digital teams separate from the core business, partly because the core culture is not conducive to experimentation. These labs might produce nice prototypes but often struggle to integrate into the main business or core systems (the “corporate immune system” problem). Additionally, a heavy governance layer presides over product changes—committees for new product approval, risk assessment, legal review— which can dilute bold ideas into bland, lowest-common-denominator outcomes by the time all stakeholders have vetted it.

For instance, many banks ended up with mobile apps that simply mirror internet banking functionality with limited flow, or they digitized a paper process without rethinking it (leading to awkward e-forms that still take 30 minutes to fill, just on a screen). This is a symptom of inside-out thinking: automating existing processes rather than redesigning around the user.

It’s notable that three-quarters of banks admitted their legacy infrastructure prevents timely UX improvements—a direct link between old core systems and an inability to iterate quickly on products. Traditional banks also have a tendency to consider innovation as a series of big projects (often in reaction to competitors or trends), e.g. a big “digital transformation project” rather than a continuous process. Once a project ends, momentum can fade.

Digital Banks: Agile Development and Continuous Innovation

Outside-in neobanks and Fintechs treat product development as a continuous, iterative process that is never truly “done.” They employ Agile and DevOps practices: small cross-functional teams (including product managers, developers, designers, data scientists and often a compliance or risk rep) work in sprints to develop features, release them frequently (sometimes in beta to a subset of users), gather feedback and then refine, and this loop repeats perpetually. By integrating all key functions in one team, digital banks can avoid the departmental handoff delays that plague traditional projects.

Notably, customer feedback is integral: app stores, social media and in-app feedback mechanisms provide a wealth of input that these banks actively monitor and respond to. It’s common for a Fintech company to push an update that directly addresses a user pain point raised in reviews (e.g., “we heard you; now you can freeze your card with one tap”). This responsiveness builds goodwill and results in a product that evolves alongside customer expectations.

An agile outside-in approach also means prioritizing features that deliver customer value, rather than those that primarily benefit the bank’s internal operations. For instance, a digital bank might prioritize developing an in-app card dispute feature (making it easier for customers to report fraud) over an internal reporting dashboard enhancement, whereas a traditional bank often does the reverse, because internal stakeholders have louder voices in an inside-out culture.

In practical terms, many digital banks adopt a “test and learn” rollout for new products: they might roll out a new service to a small region or group, measure and then expand. This reduces risk and allows for fine tuning. The result is that innovation is embedded into daily work, not shuffled off to a lab. A telling metric is deployment frequency—a digital bank might deploy code updates hundreds of times a year (or even per month in some cases), whereas a traditional bank might roll out a few big releases per year.

Each deployment is an opportunity to improve the product. This environment is well suited to leveraging emerging technologies quickly. For example, when open banking APIs became available, digital banks were quick to integrate outside accounts into their apps to give customers a holistic view. Traditional banks lagged behind because it didn’t fit neatly into their product silos and raised internal questions (Why show a competitor’s balance in our app?). Outside-in thinking answered: because it’s useful to the customer.

In summary, digital banks approach product development as customer-centric problem solving using rapid cycles. This yields more innovative features and the ability to adapt faster to new trends (like mobile wallets, P2P payments, buy-now-pay-later). It’s no coincidence that many digital banking features that are now becoming standard were pioneered by Fintech/digital challengers while incumbents took years to follow.

Governance and Product Risk

A critical implication of these approaches is how product risk and compliance are handled in development. Traditional banks separate these functions—compliance reviews are stage-gates that can halt a project late in the game. Digital banks integrate compliance as design constraints from day one, which paradoxically can produce both a compliant and user-friendly outcome.

For example, instead of a tedious compliance step added at the end of an account opening, a digital bank team might design a pleasant KYC flow that meets regulations via user experience (e.g., dynamic ID scanning, database checks in the background, etc.) so the product is both compliant and smooth. This integrated approach is encapsulated by the idea of “compliance by design.”

It’s about building risk controls into the design, instead of adding them later and organizing so that risk, compliance and business co-create solutions. Traditional banks have started to realize this, but their legacy structures make it hard to achieve. The implication is that digital banks often reach acceptable compliance faster and with less friction than an incumbent that retrofits compliance onto a new product at the end (often resulting in extra forms or disclosures that frustrate users).

Time to Market and Adaptability

The difference in product development speed has direct strategic consequences. A traditional bank might take so long to launch a new digital service that the window of opportunity is missed or competitors have already set the standard. Digital banks often pride themselves on time to market—being first (or very fast) to offer what customers are starting to want.

Moreover, adaptability means if a product or feature is not resonating, a digital bank can pivot or kill it with less sunk cost, while a traditional bank might double-down or persist due to having invested heavily in a long project (the sunk cost fallacy in slow development). This is why we observe some legacy banks continuing to push products or fees that customers hate, because they were conceived inside out (to meet a revenue objective) and took so long to build that now they hesitate to remove them, even as Fintech alternatives capitalize on customer discontent by offering fee-free or more convenient options.

Implications on Technology and Infrastructure

Technology is both an enabler and a constraint for banks, and the inside-out vs. outside-in dichotomy leads to very different tech landscapes.

The inside-out architecture leaves banks with aging core systems, fragmented data and rigid infrastructure that makes rapid change difficult and expensive. The outside-in architecture, being built on modern, flexible tech, allows neobanks to iterate quickly, integrate easily and scale efficiently, thereby serving customers better. It shifts the IT function from a cost center that “keeps the bank running” into a strategic asset that “drives innovation and customer value.”

The implication for incumbents is clear: without addressing their legacy technology (either through modernization or clever layering strategies), any attempts at digital transformation will be hamstrung. In fact, many transformation failures at banks can be traced back to an attempt to deliver a cutting-edge digital experience while still chained to a legacy core that can’t support real-time, personalized, omnichannel services. This is why core transformation is often called the “heart transplant” of a bank—daunting but increasingly necessary to truly invert the model from inside out to outside in.

Traditional Banks: Legacy Core and Integration Complexities

The typical legacy bank runs on large, centralized core banking systems that handle deposit accounting, loan accounting, payments, etc. Many of these systems are decades old, written in COBOL or other legacy languages, and hosted on mainframe or proprietary on-premises servers. They were built for robustness and batch processing, and they excel at handling high volumes securely. However, they are notoriously inflexible and costly to change.

Introducing a new product or even a small feature (like a new field in a customer profile) can be an extensive IT project touching the core. Over the years, banks layered additional systems around the core—for CRM, online banking, mobile, analytics—leading to a spaghetti of integrations and data silos. One consequence is that real-time data flow is limited; a customer’s information might be fragmented across systems that sync only periodically. This makes it hard to get a single 360° view of the customer in real time, something digital banks take for granted.

Moreover, the complexity slows down development: changes must be carefully orchestrated across interdependent systems. An apt description from a bank technology perspective is that legacy cores are monolithic, making it “difficult for banks to add new capabilities or customize” quickly. This puts a ceiling on how agile a traditional bank can become unless it addresses its core. Another tech implication is downtime and update cycles—older systems often require planned downtimes for maintenance (e.g., overnight or weekend system maintenance windows), which is increasingly unacceptable in a 24/7 digital world.

Customers of legacy banks might be familiar with not being able to use the app on Sunday midnight because of “scheduled maintenance,” a phenomenon virtually unseen in modern cloud systems. Legacy architecture also struggles with scalability and cost efficiency. To handle growth or spikes, banks might need to invest in more physical servers or mainframe capacity, which is expensive and not instantly elastic like cloud. All of this results in higher operating costs.

Studies have shown that a huge portion of a traditional bank’s IT budget goes to just maintaining existing systems (often 70%), leaving little for innovation. This tech debt directly hampers customer experience improvements and speed to market. In fact, 85% of organizations are considering switching from legacy providers to digital-first banks in search of a more seamless onboarding experience. This reflects how old tech and processes create friction for customers and push even business clients to seek more digital-friendly alternatives.

Also, because many legacy banks rely on a few big third-party core software providers, their ability to differentiate on tech is limited. They end up with similar capabilities as others who use the same vendor, unless they heavily customize (which then adds more complexity). Integration with Fintechs or third-party services is also harder for traditional banks. Many have to stand up middleware or “API layers” to connect their core to modern applications, which can be kludgy and limited.

Digital Banks: Modern, Modular Tech Stack

Digital-first banks had the advantage of building from scratch (or nearly so) in the last decade or so, and thus could choose modern technologies and architectures. They typically employ cloud-native infrastructure, hosting their systems on cloud platforms that provide on-demand scalability, resilience and a rich ecosystem of services (for storage, AI, security, etc.). This means they can scale up during high usage (say, end of month or a viral campaign) without a hitch and scale down to save cost when idle, paying only for what they use. Their application architecture is usually microservices-based, meaning the overall system is composed of many small services, each responsible for a specific function (e.g., a service for customer profile management, another for transaction processing, another for notifications).

These services communicate through APIs. This modular design has two key benefits: agility and resiliency. Agility comes from being able to update or deploy each service independently, so a change in the “notifications” service doesn’t require taking down the whole system or retesting everything; you just update that component. Resiliency comes from fault isolation: if one microservice fails, it can often be isolated or rolled back without bringing down the entire platform. Furthermore, digital banks heavily leverage APIs, not just internally but externally. They are often conceived as platforms that can connect to an ecosystem of partners.

For example, a neobank might provide APIs for Fintech apps to integrate banking services (e.g., account opening, transaction data, payments) into those apps, embracing the open banking trend or ensuring embedded banking. This can turn a bank into a platform beyond its own customer base, generating new revenue streams (through API usage fees or partnership models).

A crucial point is that modern systems can be updated continuously without downtime. A digital neobank can improve its technology behind the scenes without customers noticing service interruptions. This supports the continuous innovation approach discussed earlier. Importantly, modern core banking software (if they use a vendor or open-source core) is often built with configurability and product flexibility in mind. It might allow new product types to be launched via configuration rather than code, significantly accelerating time to market for, say, a new savings account flavor or loan variant. That is in stark contrast to older core systems that sometimes required custom coding for each new product variation.

Security and Compliance Infrastructure

Both types of banks must be extremely cautious about security and compliance given banking regulations and cyber threats, but how they approach it differs. Traditional banks, with their compliance-first mindset, have very heavy processes (e.g., manual checks, extensive documentation, periodic audits) to ensure security and compliance, which, while thorough, can slow down change and sometimes still fail to preempt issues, as evidenced by occasional major system outages or breaches in some large banks.

Conversely, digital banks, by integrating security into their tech design from the start, often use automated compliance controls. For instance, every code commit might undergo automated security scanning; infrastructure-as-code means environments are built consistently and securely; role-based access and strong encryption are standard. Cloud providers also offer many built-in security features (e.g., encryption, DDoS protection, monitoring) that digital banks utilize. Some regulators initially were wary of cloud, but now it’s well accepted that cloud can be at least as secure as on-prem, if not more, when managed properly.

Digital banks also typically provide more transparency and control to users over security (like the ability to lock/unlock cards, control what kinds of transactions are allowed and get alerts for any suspicious activity). This not only improves customer peace of mind but enlists the customer in monitoring, effectively crowdsourcing part of fraud detection (if a user gets an instant alert and flags a transaction as fraudulent, that’s a rapid response). Traditional banks have added some of these features, but often as bolt-ons rather than native design elements.

Technical Debt vs. Technical Advantage

The inside-out model has saddled incumbents with massive technical debt, not just in the core systems but in the layers of patchwork integrations and workarounds built over time. Every time a new channel emerged (ATM, then internet, then mobile), many banks simply bolted new systems onto the old, increasing complexity. The outside-in challengers designed a fresh system, often with an API-centric unified approach that handles multiple channels elegantly from a single source. The result is that incumbents sometimes spend a lot of resources on “keeping the lights on” and compliance updates for old systems (e.g., ensuring an aging core can produce new regulatory reports), whereas challengers can spend that effort on new features and growth.

A McKinsey study noted that banks urgently need new core platforms for agility, but building one is hard and time-consuming, highlighting that many banks acknowledge the need (seeing what digital players can do) but are daunted by the challenge of changing engines mid-flight. Some incumbents have started migrating to modern cores or using a “parallel stack” approach (i.e., building a new digital core alongside for new products or segments). This is effectively an attempt to mimic the challenger approach while slowly phasing out the old—a strategy we will touch on in transformation paths.

A key implication of the differing tech is cost structure. Traditional banks spend a significant portion of revenue on IT and operations—maintaining data centers, operations staff for manual processes, licensing fees for legacy software, etc. Digital banks, with cloud and automation, tend to have a much lower cost per customer once scale is reached.

For example, it’s been cited that digital banks’ cost-to-income ratios can be dramatically lower; and, as mentioned, some operate at 8x lower cost than legacy banks on certain measures. This cost advantage enables digital banks to offer attractive pricing (no or low fees, better interest) and still be viable.

Meanwhile, incumbents feel pressure on margins because they have to cut fees to compete yet carry higher costs—a recipe for squeezed profitability. This is why so many incumbent bank CEOs emphasize the need to cut costs via digitization; it’s existential in the long run. But until they truly transform the architecture, many cost reductions are superficial (closing a few branches, etc., which helps but doesn’t fully solve the structural cost issues of legacy IT and bureaucracy).

We should also note how technology choice enables or stifles innovation. Because digital banks use modular tech, if a new innovation emerges (say a new payment protocol or a new AI tool), they can integrate it relatively quickly via APIs or cloud services. A legacy bank might struggle to adopt it because their stack isn’t compatible or they’d have to do extensive integration work. This leads to a phenomenon in which incumbents are often followers in tech innovation, adopting things like mobile check deposit, P2P payments, AI chatbots, etc., years after Fintechs proved the concept. It’s not purely tech—organizational caution plays a role—but tech is a big part of the lag.

Implications on Customer Relationships and Engagement

Perhaps the most important dimension—where all the above factors converge—is the nature of the bank’s relationship with its customers. The inside-out vs. outside-in approach creates very different experiences and thus different relationships.

Traditional banks are now trying to catch up on engagement, offering financial wellness tools, trying to personalize offers, sending push notifications, etc. But often these efforts are bolted onto legacy systems and aren’t as fluid or integrated. Customers can tell when something is an afterthought versus a core design element. For instance, some banks have apps in which the budgeting feature feels like a separate module that’s not well integrated with transactions, whereas a digital bank’s whole app might be built around the concept of budgeting and insight from the ground up.

The outside-in model builds a relationship in which the bank is seen as a partner and advisor in the customer’s life, often with daily micro-interactions, while the inside-out model yields a more utilitarian DIY (do-it-yourself) relationship in which the bank is visited only when a strong need persists and is, at times, dreaded. The implications for the banks are profound: engaged customers are more profitable over time. They use more services, are more receptive to cross-sells that genuinely fit their needs, cost less to serve due to digital usage, and they refer others.

Disengaged or frustrated customers either leave or stay and treat the bank as a commodity, keeping minimal balances, not taking additional products, etc.. That is why a recent strategic focus for many banks is to shift from being product-centric to relationship-centric. But achieving that requires the kind of architectural inversion we discuss, putting the customer (outside) at the center of everything, rather than the product or process (inside).

One can encapsulate the difference in a simple analogy: traditional banking relationships are like a formal handshake: periodic, businesslike and somewhat impersonal. Digital banking relationships are like a continuous digital conversation – ongoing, interactive and personalized. The latter clearly aligns better with where consumer expectations are headed in an era of smartphones and personalized services.

Having explored these implications in strategy, product, technology and customer engagement, it becomes evident that traditional banks must transform to remain relevant. They need to adopt key elements of the outside-in architecture, essentially flipping their model, principles and approach upside down. However, this is not a trivial task. In fact, it is a monumental challenge that touches every part of the organization.

Traditional Banks: Transactional and Intermittent Relationships

Historically, customers interacted with their bank only at specific moments, depositing paychecks, visiting a branch for a loan, checking monthly statements, etc. In an inside-out model, the bank’s engagement with customers is largely transaction-driven..

Customers come to the bank when they need a product or service, and the bank fulfills that need through its processes. If everything works, the interaction ends there until the next need. There is relatively little proactive outreach beyond marketing new products or the occasional service alert. Part of this is cultural (banks didn’t want to “bother” customers too much, and had nothing personalized to say), and part technological (hard to analyze customer data for personalized insights in legacy systems). The consequence is that many customers saw their bank as a utility: necessary but not particularly engaging or loyalty-inspiring.

Trust in traditional banks was based on reliability (will my money be safe? will they be there in 30 years?) rather than on delight or emotional connection. A compliance-first mindset also sometimes leads to customer-frustrating policies, like rigid fee penalties or making customers jump through hoops for security in a visible way. This mindset, while serving the bank’s risk goals, eroded goodwill. Traditional banks, being process-driven, often expected customers to adapt to the bank’s processes.

For example, if the bank was only open 9-5 on weekdays, the customer had to make arrangements to visit during that window. If onboarding required a 10-page form, the customer had to fill it in. This dynamic puts the onus on the customer, creating friction and a perception of the bank being somewhat indifferent to the customer’s time or convenience.

Not all traditional banks had poor customer service; many prided themselves on friendly staff and personal touch, especially for known clients. But that personalized service was usually limited to the branch context or certain segments (like wealth management for high net-worth clients). The average retail customer of a big bank might rarely talk to a human who knows them; most interactions could be with ATMs or generic call center operators. Customer-centric metrics historically were low; indeed, surveys over the years often found banks (especially big ones) scoring low on customer satisfaction relative to other industries.

For example, in recent US customer experience indices, many traditional banks had mediocre rankings, with user comments often citing clunky digital interfaces or “bank bureaucracy” as pain points. There’s also the issue of trust in advice: traditional banks would push products (like credit cards or loans) as part of sales campaigns, which savvy customers understood as cross-selling rather than genuine care.

This built a skeptical relationship: customers didn’t necessarily see their bank as a financial advisor aligned with their best interests, but rather as a vendor of financial products. Therefore, loyalty was often shallow—many customers stayed due to inertia, difficulty of switching providers or lack of local alternatives, not because they loved their bank. The rise of Fintech alternatives made this evident as customers began switching for better service or user experiences, which they might not have contemplated earlier.

Digital Banks: Engaged and Holistic Relationships

In the outside-in model, the bank strives to be an integral part of the customer’s daily life. The relationship is much more continuous thanks to digital channels. For instance, a customer of a digital neobank might check their app multiple times a week (or day) for spending updates, use their card for all purchases (getting instant notifications), interact with savings tools, make investments, assign to financial products, etc., right from the home in minutes. Each of these digital micro-interactions reinforces the relationship. Done well, it builds a sense of partnership—the bank is actively helping the customer manage money, not just passively holding deposits.

Digital banks also often adopt a more customer-friendly tone and approach. Their communications are usually in plain language, even playful at times, rather than filled with legalese. This humanizes the relationship and shows real care. Features like in-app chat support available 24/7 mean customers feel the neobank is always there for them. And because digital banks leverage data smartly, they can proactively reach out with useful insights or offers.

For example, a digital bank might notify a customer: “We noticed your paycheck is a bit higher this month. Consider moving some to savings; we’ll help you set it up.” Or: “You have a subscription that increased its price; tap here to review if you still need it.” These kinds of context-aware engagements make customers feel the bank is looking out for them. That is a far cry from the generic mass emails traditional banks might send.

Personalization at scale is a key hallmark of digital relationships—each customer can feel uniquely served by technology, something legacy banks tried to do via human managers for a select few. Research supports that personalization drives engagement: 61% of consumers are more inclined to spend with companies that provide personalized experiences, and banks are tapping into this via digital means.

The emotional connection in a purpose-led bank is stronger. If the bank’s brand stands for something (e.g. financial inclusion, or empowering people to achieve goals), and the customer experiences that in practice through the app and services, it creates affinity. Many Fintechs have almost cult-like followings initially, with customers referring to friends enthusiastically, something rarely said of a traditional bank.

Indeed, one measure of relationship strength is NPS (Net Promoter Score), and, as noted, digital banks often enjoy NPS scores multiple times higher than incumbents. For example, some neobanks reported NPS in the +50s or +60s (very high), whereas many big legacy banks hover around 0 to +20 in some markets. While NPS can vary by country and other factors, the gap indicates a difference in customer sentiment: digital bank customers are more likely to recommend their bank to others because they genuinely find it better or aligned with them.

Trust and Transparency

Trust is foundational in banking; customers need to trust that their money is safe and their data protected. Traditional banks have long held the upper hand in trust regarding security being established and regulated, but they lost trust in being customer-aligned (especially after events like the 2008 crisis or various misselling scandals).

Digital banks had to earn trust from scratch, which many did by being more transparent and fair in their policies (e.g., simple fee structures or no hidden fees at all, real-time transaction alerts, preventing surprises). Some digital banks incorporated features like in-app control (e.g., you can toggle whether your card is allowed to do online transactions, foreign transactions, etc.) which puts customers in control, thus building trust.

They also often have very responsive customer service (leveraging chatbots for quick answers and humans for complex issues), which increases trust that if something goes wrong, it will be resolved quickly. Traditional banks sometimes suffered here; for instance, long call center wait times or bureaucratic procedures to dispute a charge can erode trust.

Community and Feedback

Another interesting development with outside-in players is building a sense of community. Some neobanks engaged customers in their development—through community forums or beta testing groups—effectively co-creating with them. This not only yields useful feedback but also makes customers feel a sense of ownership or belonging with the brand. Legacy banks rarely did this; product changes were decided in boardrooms, not in consultation with everyday customers. By incorporating the customer voice in their evolution, digital banks strengthen the relationship and ensure they remain aligned with customer needs (truly outside-in).

Loyalty and Retention

A direct benefit of higher engagement and satisfaction is increased loyalty. Customers of digital banks might consolidate more of their finances with that bank because it’s simply easier and more pleasant. For example, if the app provides a great budgeting tool that works best when you use that account for all spending, customers will naturally channel more of their deposits and transactions there.

Traditional banks historically relied on “sticky” products (like a checking account that is hard to switch due to direct deposits and bill pays, or inertia) to retain customers, rather than delight. But we see that, increasingly, experience is the new loyalty program. If your service is consistently convenient and helpful, customers stay. Conversely, when friction or pain accumulates, they leave. It’s telling that a report noted a large percentage of customers cite their bank’s online/mobile platform quality as a key reason for staying or leaving. In fact, 82% of bank customers said their institution’s online and mobile quality was a key reason for staying with the bank. This underscores how critical the digital experience has become to customer retention and, by extension, to relationship depth.

The Transformation Challenge: Inverting the Model from Inside-Out to Outside-In

For incumbent banks, moving from a traditional architecture to a next-gen digital architecture is often compared to “turning a supertanker” or “changing the jet engine mid-flight.” These metaphors underscore the complexity and risk involved. The transformation challenge is not merely about new technology or a fresh coat of paint on the mobile app; it is about fundamentally changing the operating model, culture and systems of the organization— effectively inverting the pyramid of how the bank works.

Many banks have struggled to truly become digital-first. There are notable cases in which banks poured money into digital transformations that didn’t yield expected results, often because one or more of the above challenges was not fully addressed (e.g., cultural resistance derailed it, old systems proved too hard to integrate, etc.). A Finextra analysis by Alex Kreger highlights that often brilliant boardroom strategies vanish by the time they reach execution because “few organizations are structured to close” the gap between ambition and execution. This is precisely the transformation gulf: having the vision to be outside-in is one thing; actually doing it through the layers of a legacy bank is another.

However, it’s not impossible. Banks that have succeeded (or made substantial progress) tend to approach it holistically: tackling tech, process and culture together, often in a multi-year phased journey. They accept that transformation is not a one-time project but a continuous evolution. They also often seek external help (e.g., consultants, partnerships with Fintechs, hiring from tech firms, etc.) to inject new perspectives.

One strategic approach many adopt is “two-speed” or “bi-modal” transformation, keeping the core business running (improving it incrementally to stay competitive) while simultaneously driving a faster digital initiative that can innovate more freely. Some do this via a separate digital subsidiary (as discussed in Jim Marous’s article on digital twins), essentially building a digital bank within the bank. This can create room for new culture and tech but also has downsides like internal competition or duplication of effort. Some separate units have flopped or had to be folded back in later. The success seems mixed—it’s not a panacea—but when done well, it can catalyze change, and when done poorly, it just creates an isolated island that never scales.

Ultimately, the transformation challenge boils down to this insight: traditional banks must fundamentally invert their perspective—from inside-out to outside-in—which requires reimagining their core systems, product logic, processes and culture. It’s a shift from an operational mindset (efficiency, control, status quo) to a design mindset (empathy, experimentation, purpose). And it’s incredibly challenging because it asks an institution to almost become something it wasn’t. But it’s also a survival imperative.

As Jim Marous, banking influencer and The Financial Brand founder said: "Culture is key to digital transformation in banking, not technology." This captures the essence: technology and processes can be bought or copied, but without the organizational and cultural will to change, the transformation will stall. Conversely, a bank that genuinely commits to an outside-in philosophy will find ways to overcome technical and regulatory hurdles because the entire organization will be aligned toward that goal.

Having acknowledged how challenging this is, the obvious question is how to actually do it. Therefore, in the next section, we outline a strategic path to transformation, which provides a roadmap for traditional banks looking to invert their architecture and mindset in a manageable, effective way.

Cultural and Organizational Inertia

Changing mindsets is hard. Leaders and employees alike have “the way we do things” imprinted from years or decades of working in a particular manner. Incentive structures often reinforce old behaviors (e.g., rewarding branch managers for product sales rather than customer satisfaction).

Furthermore, in many banks, being innovative or questioning established processes was historically discouraged, so employees may be reluctant to embrace new ways, even if told to do so. A purpose-led, customer-focused approach may even sound suspect or fluffy to veteran bankers who rose through the ranks by focusing on numbers and compliance. Overcoming this requires strong vision from the top, often bringing in new talent who embody the desired culture as well as retraining existing staff. Some banks have found it useful to create cross-functional agile teams or “tribes” that operate with a new set of principles, essentially seeding a new culture within the old. But scaling that across the whole enterprise is challenging.

There is often internal resistance: business unit heads protecting their turf, mid-level managers afraid of losing status if hierarchy flattens, compliance officers nervous about faster experimentation, etc. As Jim Marous noted, many organizations struggle because leadership may be “willfully blind” to the depth of change required, and employees don’t feel empowered to take risks or challenge the status quo. So cultural transformation must come before or at least alongside any tech changes. Without it, new technology or processes will be grafted onto an old mindset and will likely be underutilized or misaligned.

Legacy Core Systems and Tech Debt

We discussed the burden of legacy technology. Transforming this is akin to performing “heart surgery” on the bank. Banks face a tough choice: replace core systems (a risky, multi-year project that’s been likened to changing the tires on a moving car), gradually modernize by modules (e.g., keep the core ledger but replace surrounding systems with microservices and progressively encircle the old core until it can be switched off), or build a parallel digital bank from scratch (and later merge or migrate customers).

Each approach has its pros and cons, but none is easy or cheap. A full core replacement can cost hundreds of millions and has led to high-profile failures or write-offs in some cases, making some bank boards very wary. However, avoiding it indefinitely is also dangerous as the cost of patching old systems and the opportunity cost of missing agility mount. Some banks have found success in starting with a “sidecar core,” e.g., launching new products on a modern core platform while still running existing ones on the old core, thereby learning and gradually moving volumes over. This two-speed architecture allows incremental transformation.

Regardless of method, rethinking architecture is key. Banks likely need to embrace cloud with appropriate security and regulatory compliance, which is increasingly doable as regulators have warmed to cloud deployment, and banks have developed robust risk frameworks for it. They need to implement API layers and microservices to decouple customer-facing innovation from core transactions. Essentially, they must create a platform that can respond in near real-time to customer and market demands. This often means simplifying decades of accumulated complexity, for instance, consolidating multiple product systems into a single integrated system or standardizing processes group-wide so that one technology solution can serve all.

Siloed Product and Business Structures

As discussed, traditional banks are usually siloed by product or channel. To become outside-in, they must reorganize around customer segments or journeys. This reorganization faces internal political challenges. It means, for instance, dissolving or integrating product departments into broader teams focused on an end-to-end journey (like “home ownership journey” covering mortgages, home insurance, etc., or “SME business growth journey” covering various needs of small businesses). It requires leaders of former silos to either cooperate or yield to a new structure.

Often there’s overlap and redundancy in an incumbent bank—each product team might have its own marketing, tech budget, etc.—and moving to a customer-centric structure can reveal these and lead to consolidation (some people may lose roles or get re-assigned, which creates resistance). Product governance also has to change: instead of separate committees for every product line, a more integrated governance that looks at the customer’s holistic portfolio or journey is needed. That can streamline decision-making but only if the organization genuinely adopts it. Otherwise, decisions get bottlenecked because now more stakeholders are involved in an “integrated” committee rather than the simpler silo one.

So governance must be carefully redesigned, not just lumping all old committees into a bigger one. The transformation challenge is essentially to break down walls between departments, IT and business, channels, which is as much a people issue as a process one. The bank’s organizational chart may need to be redrawn, often flattening it and creating more cross-functional squads that operate with autonomy.

Mindset: From Compliance-Only to Balanced Purpose and Compliance

A notable transformation is shifting the mindset that “compliance and risk are everyone’s job, done in an agile way” rather than “compliance is the police that tells us no at the end.” Traditional banks often have an adversarial dynamic between business (wants speed) and risk/compliance (wants caution). In a truly transformed model, they work as partners with a shared goal: serve the customer in a safe way. That might involve new processes like including compliance officers in design sprints or using “risk by design” checklists during ideation.

It’s encouraging that experts suggest building compliance into each sprint or product iteration. But again, making that cultural shift in which compliance is not just about saying no but about finding safe ways to say yes, is non-trivial. Regulators, too, are part of the puzzle; banks must work with regulators to get comfortable with new approaches (for instance, using cloud, using AI in credit scoring, etc.). Increasingly, regulators encourage innovation (sandboxes, etc.), but banks must navigate these relationships carefully during transformation.

Short-term vs. Long-term Focus

Inverting the model is a long game, but banks are public companies that need to hit financial targets regularly. There’s often a short-term pressure that conflicts with a long-term transformation investment. For example, fully revamping a core or digital experience might depress earnings for a few years due to high investment and possibly running duplicate systems during migration.

This fear sometimes leads banks to hesitate or choose half measures. The transformation challenge is to overcome the instinct to protect short-term profits or avoid all risk, instead taking calculated risks for future viability. Not doing so is itself risky as one BCG piece warned, “Banks need to start acting like digital giants before digital giants act like banks.” In other words, the cost of inaction is being overtaken by big tech or agile Fintechs. This burning platform can be used as a motivator, but it needs to be internalized at all levels.

Employee Skills and Change Management

The people aspect extends to skills. A bank transforming to a tech-driven, customer-centric model will need different skills (more data scientists, UX designers, agile product owners, etc.) and fewer pure paper-pushing administrative roles. Reskilling programs and hiring new talent are both required.